Table of Contents

ToggleTime Capsules

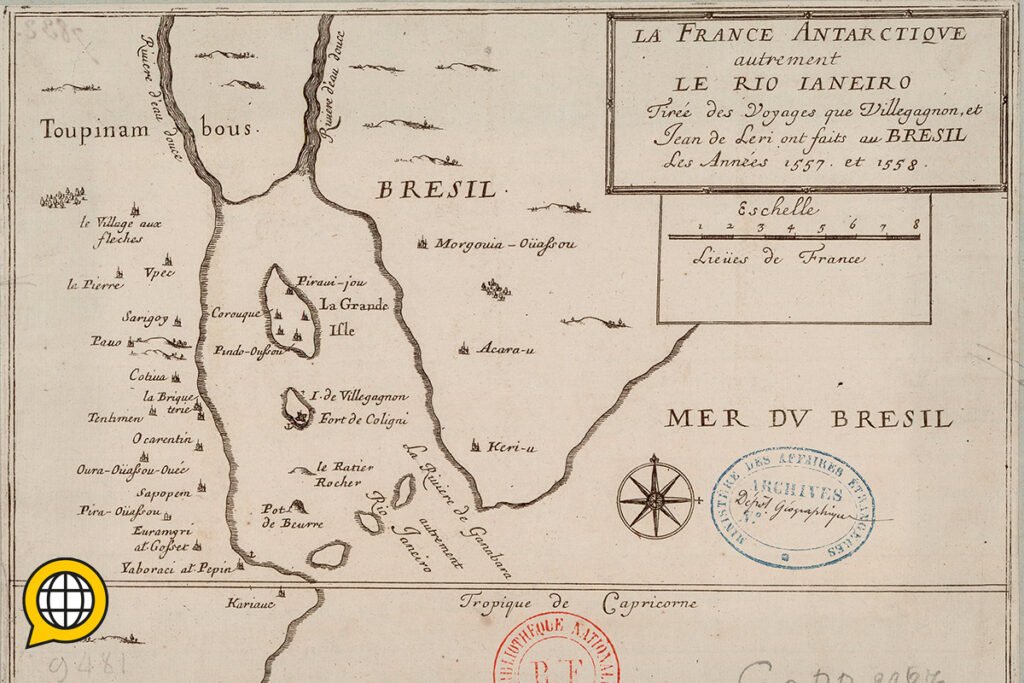

- 1555: France Antarctique Sparks Rio’s Birth - French admiral Villegaignon lands with 600 settlers, including Huguenots, to build Fort Coligny in Guanabara Bay.

- 1560–1567: Porgugal fights back - Portugal panics, fights back, and sends Governor Mem de Sá to shell the French fort. The French were finally expelled by his nephew Estácio de Sá, who founded the city of Saint Sebastian of Rio de Janeiro in 1565.

- 1710: Duclerc’s Failed Raid Sets the Stage - French buccaneer Jean-François Duclerc loots Rio but gets trapped by militia at Morro do Castelo, the center of Old Rio. He is arrested and dies in prison.

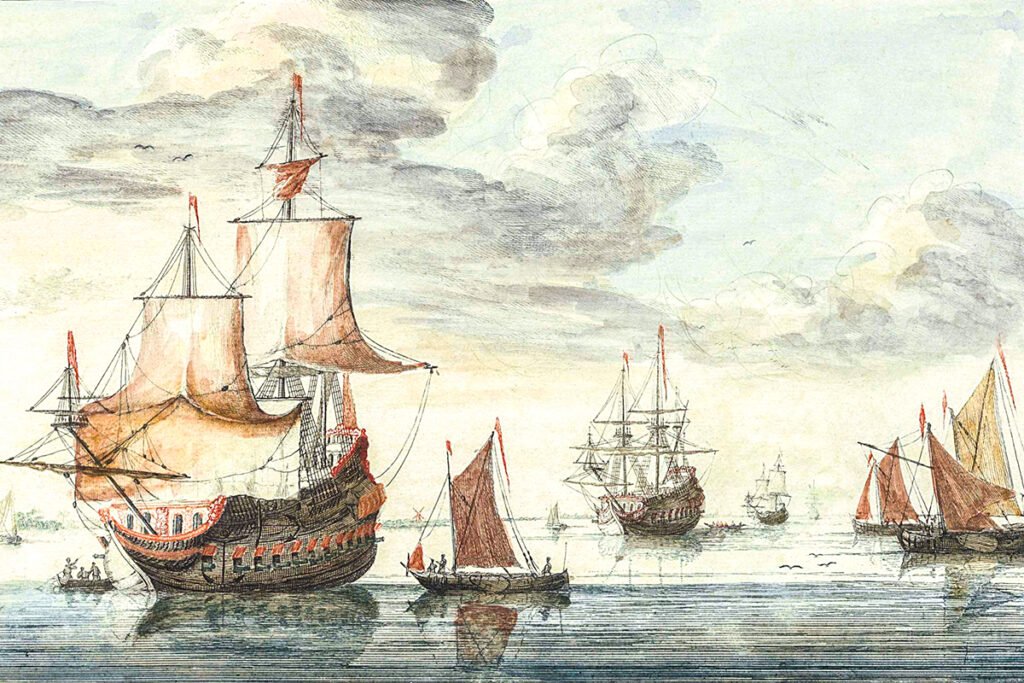

- September 1711: Duguay-Trouin’s Pirate’s Precision - Corsair René Duguay-Trouin uses mist to dodge forts and storms in with 17 ships. He bombards Rio for days and holds the city hostage for gold and sugar.

- 1711: Ransom Shakes Rio Awake - Portugal pays up, then fortifies the city, eyeing its future. France doesn’t stay, but Rio’s vulnerability turns it into a priority.

- 1808: Royal Rio - Before Napoleon reaches Lisbon, Prince Ruler Dom João VI flees with the Royal Family and many court members to Brazi. Their arrival caused profound changes in the city.

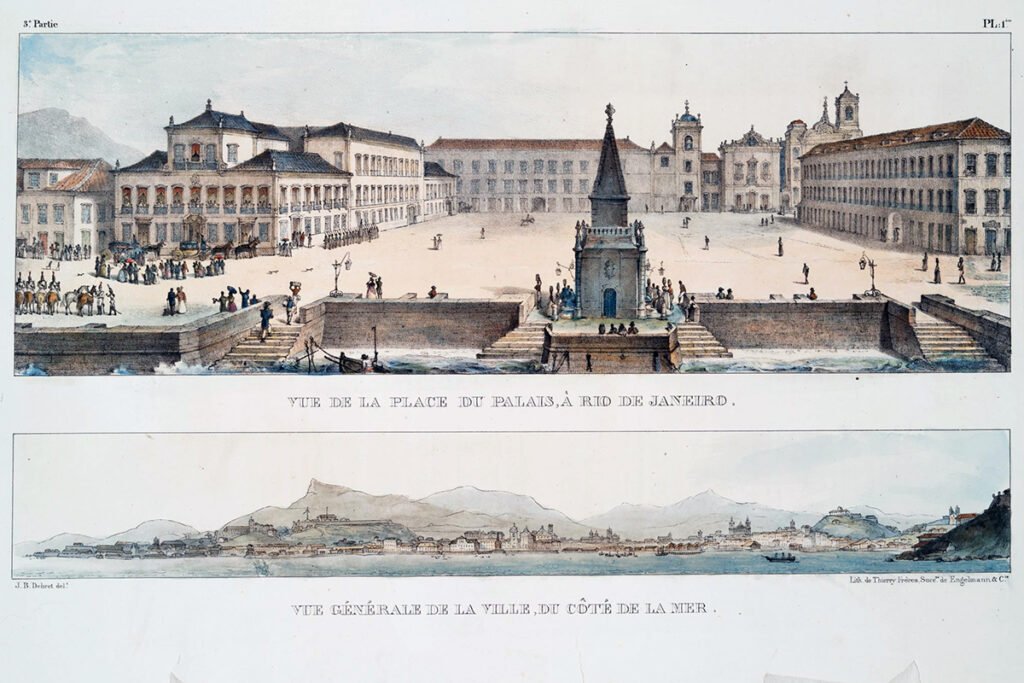

- 1816: French Artists Arrive in Rio - Post-Napoleon, Dom João VI hires the French Mission — painters like Debret and architects like Grandjean — to polish Rio into an imperial capital.

- 1816–1821: A Cultural Makeover - Grandjean’s neoclassical designs transform Rio, while Debret’s sketches and notes detail life during that period. —France doesn’t fight, but their art and ideas stick, shaping its imperial glow.

- France’s Triple Legacy - Three French interventions — colony, raid, culture — failed to claim Rio but molded it. A birthplace, a wake-up, a facelift, all paving the way for the city we adore.

- A Toast to the Underdog - Next time you’re in Rio, tip your hat to France — not just Portugal’s foe but a reluctant co-creator of its vibrant heart.

A Story in Three Acts

When you conjure Rio de Janeiro—its golden sands, the thrum of Carnival, or Christ the Redeemer gazing over Guanabara Bay—Portugal naturally takes the spotlight. They “discovered” it in 1502, planted their flag, and turned a swampy bay into an imperial jewel. But France? They’re the unsung wildcard in Rio’s story, crashing the party not once, not twice, but three times, each move leaving a mark as indelible as a samba beat.

Far from mere invaders or losers in colonial tug-of-war, the French—through defiance, daring, and a dash of cultural flair—helped forge the Rio we know today. Let’s unravel these entanglements—1555, 1711, and 1816—and discover how France, often the underdog, became a silent architect of a city that pulses with life.

Act One: France Antarctique

On November 10, 1555, a French fleet slips into Guanabara Bay under a gray dawn. Leading the charge is Nicolas Durand de Villegaignon, a battle-hardened admiral and knight of Malta, with 600 souls in tow—sailors, soldiers, and Huguenot refugees fleeing Catholic France’s crackdowns. This isn’t a royal armada waving King Henry II’s banner; it’s a private venture, bankrolled by merchants and given a quiet nod from a distracted crown. They drop anchor on a tiny island—now Villegaignon Island, a speck near Rio’s modern airport—and throw up Fort Coligny, a wooden stronghold amid mangroves and relentless heat.

Villegaignon’s crew isn’t alone. They strike a deal with the Tamoio, a Tupi-speaking people who rule the bay’s shores, trading muskets and mirrors for fish and manioc. The Tamoio, already bristling at Portuguese slavers, see the French as useful allies. The colony, dubbed France Antarctique, dreams big—a Protestant haven, a Brazilwood hub—but it’s a mess from the start. The island’s too small, fresh water’s scarce, and crops wither. Villegaignon, a Catholic turned reformer turned tyrant, sows chaos: by 1558, he’s executing three Huguenots for dissent, shattering the colony’s fragile unity. He bails back to France in 1559, leaving a skeleton crew to fend for themselves.

Portugal, meanwhile, has been napping on Rio since Gaspar de Lemos sailed by in 1502, mistaking the bay for a river’s mouth—hence Rio de Janeiro. France Antarctique jolts them awake. In 1560, Governor Mem de Sá, based in Salvador, storms in with 26 ships and 2,000 men, including Temiminó allies. Cannonballs reduce Fort Coligny to splinters, but the French and Tamoio dig in on the mainland, building forts like Uruçu-Mirim. It takes Mem’s nephew, Estácio de Sá, to seal the deal. Landing in 1565 with 400 fighters, he sets up camp between the Carioca River and Sugarloaf Mountain on March 1—Rio’s official birthday. Two years later, in 1567, he routs the last French-Tamoio holdouts, dying from an arrow to the face but cementing Portugal’s claim.

The French lose, but here’s the twist: without their audacious squat, Portugal might’ve left Rio a sleepy brazilwood outpost. Villegaignon’s flop forces a founding—Rio owes its first breath to French defiance. Call it an accidental gift from a failed dream.

Act Two: Corsaire Extraordinaire Duguay-Trouin (1711)

Fast-forward to September 12, 1711, and France is back—this time with cannons blazing and a pirate’s grin. René Duguay-Trouin, a Breton corsair turned national hero, sails into Guanabara Bay with 17 ships—seven warships, six frigates, and a swarm of support boats—packing 738 guns and 6,139 men. It’s the War of the Spanish Succession, and France, allied with Spain against Portugal and Britain, is broke. Louis XIV, unable to fund a proper navy, unleashes privateers like Duguay-Trouin, bankrolled by Saint-Malo merchants and nobles like the Count of Toulouse to the tune of 700,000 livres. Their target? Rio, not yet Brazil’s capital (Salvador holds that title), but a gold pipeline from Minas Gerais, ripe for plunder.

Duguay-Trouin isn’t the first Frenchman to try. In 1710, Jean-François Duclerc botched a raid—sneaking in under fog, looting for days, only to get cornered by militia at Morro do Castelo and clapped in irons. He’s dead by 1711, murdered in jail under murky circumstances. Duguay-Trouin studies the playbook and flips it. Shrouded in mist, his fleet breaches the bay’s narrow mouth, shrugging off volleys from forts Santa Cruz and São João. For nine days, he bombards Rio, seizing Ilha das Cobras and watching Governor Francisco de Castro Morais flee inland, praying for São Paulo reinforcements that never show. By September 21, the city’s his—locals cower as French boots tramp through muddy streets.

On October 10, Rio caves, coughing up a ransom that’s pure pirate lore: 610,000 cruzados in gold coins, 100 crates of sugar, 200 cattle—a haul worth millions today. Duguay-Trouin even snags a slave shipment, later sold in Cayenne, French Guiana. He sails off on November 13, losing two ships and half the loot to Atlantic storms, but still nets his backers a 92% profit. France doesn’t plant a flag, but the raid’s a wake-up call. Portugal sacks Castro Morais, exiling him to India, and doubles down on Rio’s defenses—new forts, more guns. The city’s vulnerability is exposed, its value undeniable. Gold keeps flowing, and Rio’s star rises, setting the stage for its imperial leap in 1808. Duguay-Trouin’s swagger doesn’t claim Rio, but it proves its worth—a French heist that nudges history forward.

Act Three: The French Mission and Rio’s Imperial Makeover (1816–1821)

Now it’s 1816, and France arrives not with swords but with paintbrushes and blueprints. Napoleon’s toast—exiled to St. Helena after Waterloo—and Portugal’s royal family, led by Dom João VI, has ruled from Rio since fleeing Lisbon in 1808. On March 7, that year, 15,000 courtiers turned Rio into the capital of the United Kingdom of Portugal, Brazil, and the Algarves—a first for the Americas. João, safe in Quinta da Boa Vista, wants more: a city worthy of an empire, not a colonial dump. Enter the French Artistic Mission, landing on August 12 aboard the Calpe with 40-odd talents—painters, architects, sculptors—hired to gild Rio’s rough edges.

Leading the pack are Jean-Baptiste Debret, a painter trained under Jacques-Louis David, and Auguste-Henri-Victor Grandjean de Montigny, a neoclassical architect. Debret’s watercolors—slaves hauling carts, Tupi women weaving, royal parades—capture Rio’s soul, later published as Voyage Pittoresque et Historique au Brésil. Grandjean designs the Praça do Comércio and teaches at the Royal School of Sciences, Arts, and Crafts, planting seeds for Brazil’s artistic elite. Others, like Nicolas-Antoine Taunay, paint lush landscapes, while Charles-Simon Pradier engraves coins. They’re not invaders—they’re employees, paid 1,200 milréis a year by João to civilize his tropical court.

Why French, when Napoleon chased João out? Timing and taste. Post-1815, France’s Bourbon restoration under Louis XVIII leaves artists like Debret jobless—João poaches them cheap. Portugal’s elite already adore French culture—Carlota Joaquina, João’s Spanish wife, pushes for Parisian polish over British grit. The Mission’s impact is subtle but deep: neoclassical buildings rise, streets widen, and Rio’s first art school trains locals like Manuel de Araújo Porto-Alegre. When João sails back to Lisbon in 1821, leaving Pedro I to declare independence in 1822, Rio keeps its imperial sheen—capital of Brazil until 1960.

France’s Legacy in Rio

Three strikes, three wins—sort of. France Antarctique flops but births Rio. Duguay-Trouin loots and leaves but proves its mettle. The French Mission gilds it without firing a shot. Portugal claims the victory lap, but France’s fingerprints are everywhere—in Rio’s founding, its fortifications, its facades. Next time you sip a caipirinha by Copacabana, raise a glass to the French—not just rivals, but reluctant midwives to a city that dances to its own beat. Their losses built a legacy—Rio’s as much theirs as anyone’s.